Is there ever a bad time to invest?

Markets have been relatively quiet of late: even after April, the much-analysed ‘60:40’ mix of US stocks and bonds has risen a further ~4% in 2024 to date. But as 2022 reminded us, there are periods when it doesn’t pay to be invested – and sometimes they have lasted a while.

And with geopolitics still tense and interest rates poised to remain higher for longer, seasonal talk of ‘selling in May’ – a popular idea which is only loosely based on historic experience – is with us again. For the first time in years, cash has more going for it than nominal stability as ‘normal’ interest rates have returned (‘cash’ here refers to interest-bearing deposits, not notes and coins).

Of course, no one knows, or can know, what comes next. However, as Elroy Dimson, co-author of Triumph of the Optimists, recently suggested: ‘the farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see’ (a quote attributed to Churchill).

And so here we take a long-term look at periods when it hasn’t paid to be invested – when the returns on liquid assets might have beaten those available from a mix of securities. The good news (so far) is that in each case such periods have followed episodes in which either the macro or geopolitical backdrop was deeply unfriendly, or valuations had become seriously stretched by the standards of the day – more so than they might be now.

The three key assets for investment portfolios are stocks, bonds and (interest-bearing) cash. Genuine alternatives to these are scarce – and historical data on their performance is even scarcer. But for many investors, the fabled balanced ’60:40’ portfolio (comprising 60% US stocks and 40% US treasuries) is the diversified bedrock of most investment strategies.

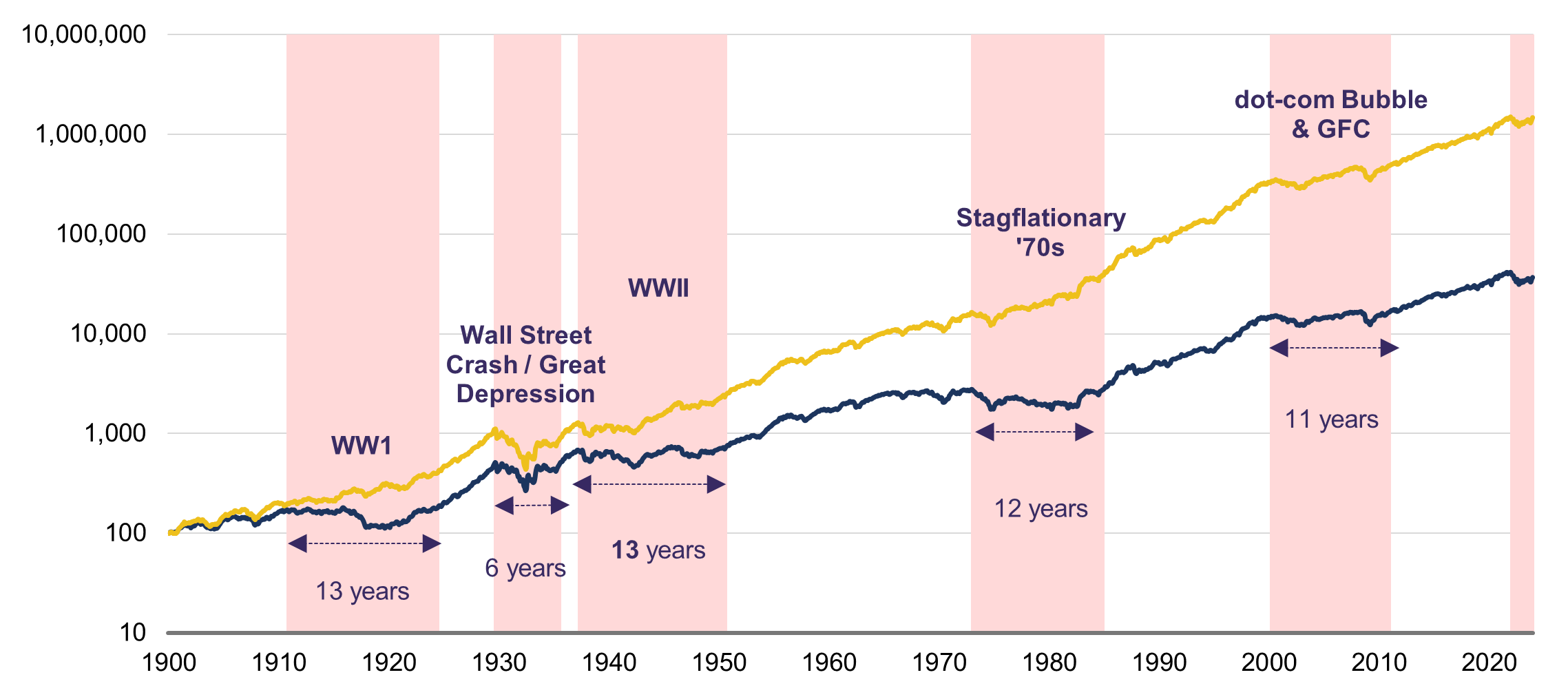

Such a strategy would have returned ~5% above inflation (on an annualised basis) over the past 120 years or so – the equivalent of doubling your ‘real’ investment every 15 years. And though this ‘60:40’ portfolio would have returned less than the 6.6% ‘real’ return delivered by a stocks-only portfolio, this would have been achieved with just over half of the volatility. By contrast, cash would merely have kept pace with inflation (+0.3% ‘real’, annualised): it’s prized liquidity in times of stress has less utility over long-time horizons. The reality is that more money has been lost waiting for the crash, than the crash itself.

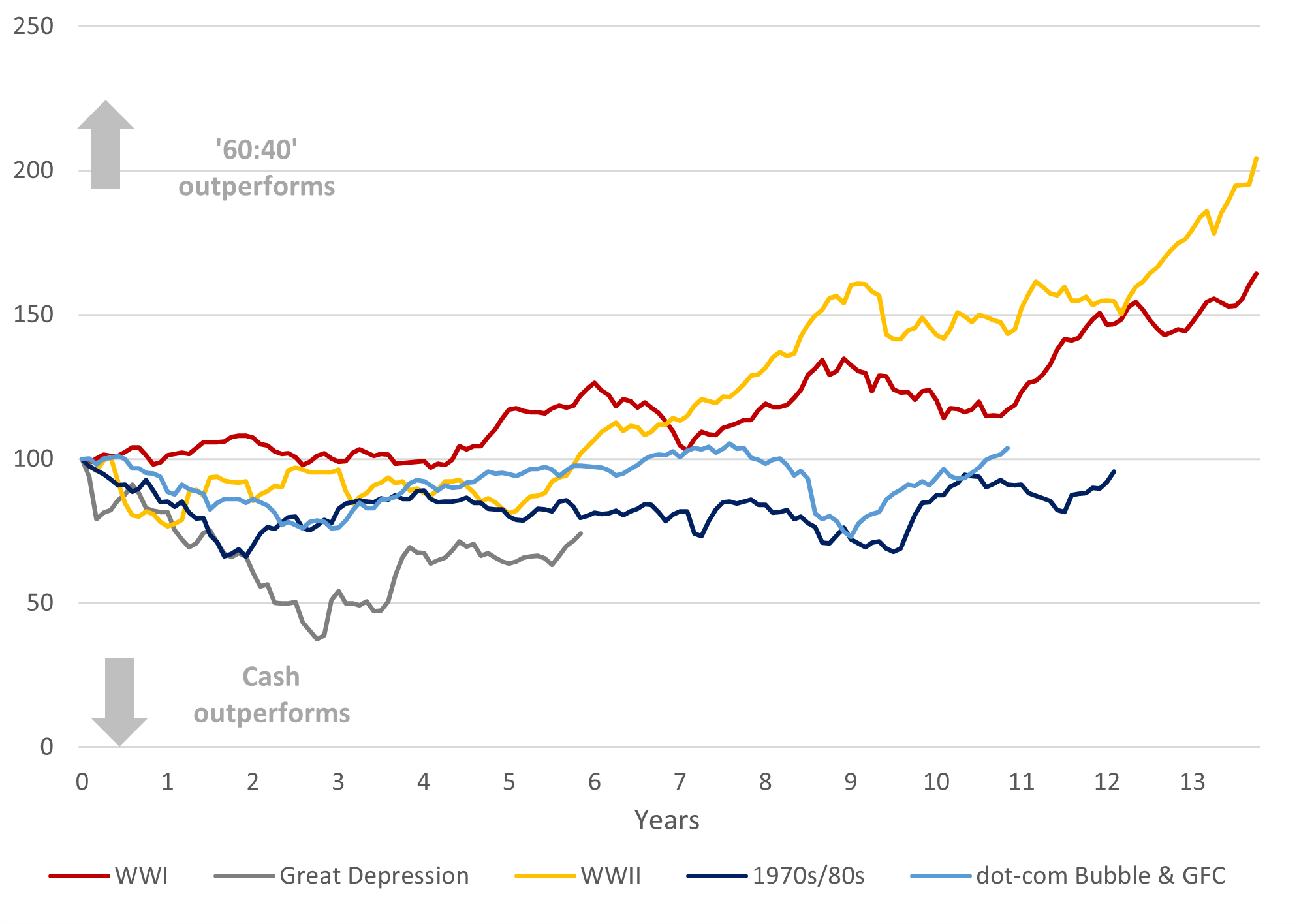

But there are exceptions to the rule. By our count there have been five extended episodes where balanced portfolios of stocks and bonds would have lagged inflation for more than a decade - with the exception of Great Depression episode, which was closer to six years. In each of these instances, the average ‘balanced’ portfolio lost more than one third of its inflation-adjusted value.

US ’60:40’ balanced portfolio cumulative returns

100 = Jan 1900, log scale

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Shiller

Portfolio comprises 60% US stocks and 40% 10-year US treasury bonds, rebalanced monthly. 'Real' returns adjusted for US inflation

There is little that these episodes share in common. Whether it’s the underlying triggers – war, frothy markets and financial accidents – or even the movements in stock and bond prices, where correlations have remained anything but stable. Depending on the mix of growth and inflation – and what impact they had in shaping interest rates – stocks and bonds delivered very different outturns in each episode.

Undoubtedly the most damaging stock market episodes were the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the more recent 2000 dot-com bubble (compounded later by the arrival of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis). In both episodes, the damage to balanced portfolios was partly insulated by the corresponding surge in bond prices, which halved the peak-to-trough drawdown. By contrast, the painful 1970/80s episode – with its runaway inflation and surge in real interest rates – hit both stocks and bonds.

But it’s not entirely clear that stuffing cash under the mattress (as it were) would have protected you – and much depends on your timing. For example, in the first of those four periods – around the time of the First World War – cash failed to outperform an invested portfolio. At the time, inflation was high, but with interest rates (intentionally) lagging, cash delivered the worst ‘real’ return of the three big asset classes.

Even during the other four grim episodes it would have required a rapid portfolio restructuring to benefit from the relative safety of cash. Unsurprisingly, most of the outperformance occurs in the first 12-24 months, after which the invested portfolio outperforms. As they say, if you’re going to panic then make sure you panic early.

Selected drawdown episodes: balanced portfolio vs cash

Indexed relative returns

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Shiller

As for those savvy market timers, loss aversion is a potent behavioural force and perhaps the biggest obstacle to compounding long term returns. It's not just knowing when to sell, but it also requires courage to reinvest that cash after the big fall has occurred. The more time that passes, the greater the likelihood that inflation will erode your purchasing power – and as markets begin to recover, the opportunity cost of holding cash becomes ever more apparent. Staying the course is often the best course of action.

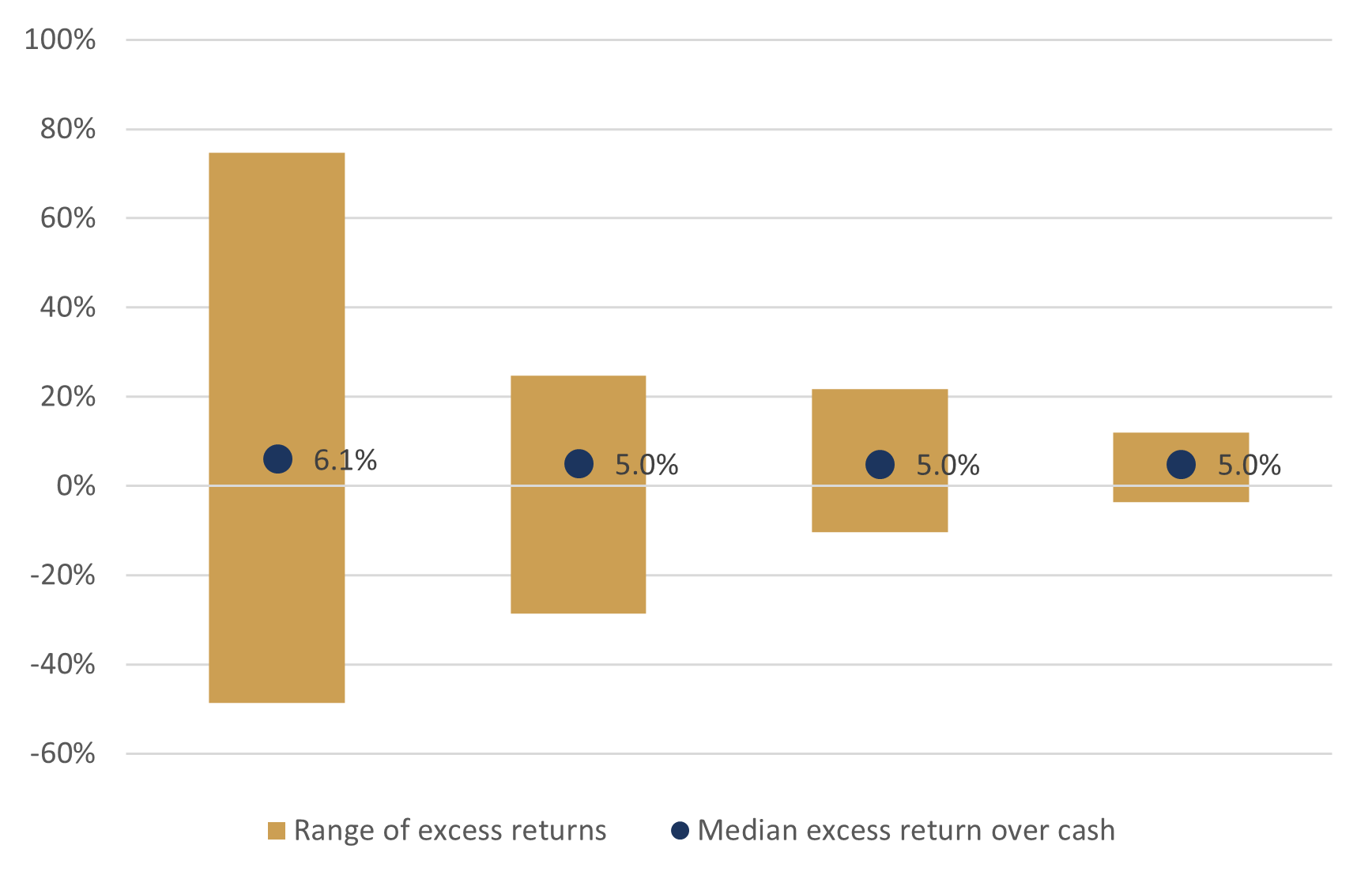

Of course, investing is not binary. Few investors will have the appetite – or conviction – to move from a fully invested position to cash (or vice versa). Even today, though uncertainty and interest rates are high, it’s not clear that ‘cash is king’. While there can be no doubt about the relative merits of the invested portfolio over the long term, even over shorter investment time horizons – such as one year – a balanced portfolio has outperformed cash more than two thirds of the time, and much more frequently over the longer 10-year rolling window.

Balanced portfolio: excess annualised returns over cash

Rolling periods: 1910 to 2023 (monthly observations)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Shiller

Our primary objective as wealth managers is to preserve and grow the real value of our clients' assets over the longer term. While cash rates today offer returns in excess of inflation, that may not last. Today, the relative appeal of stocks and bonds is closer than in it has been for quite some time, but neither are significantly ‘expensive’. Prospective returns for global stocks over the next 10 years – the period for which we estimate such returns – is close to 6% (and well in excess of prospective inflation at 2.1%). Meanwhile, the revival in bond yields – the 10-year Treasury yield at 4.5% (10-year gilts at 4.2% and 10-year Bunds at 2.5%) - suggest they also likely to clear the inflation hurdle, and perhaps offer a more credible form of diversification.

While there may be plenty of reasons for treading cautiously when investing, keeping your cash under the mattress is rarely a good investment strategy. As cliched as it may sound, time in the market beats timing the market.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.