Tariffs redux?

The Biden administration has hiked tariffs on imports from China across a variety of critical sectors.

The tariff rate on China’s electric vehicles will quadruple this year to 100%, it was announced last week, while that on semiconductors will double to 50% by next year. Other affected Chinese exports included steel and aluminium, batteries, critical minerals, solar cells and medical products. The move was a retaliation to alleged unfair trade practices by China: extensive subsidies and ‘dumping’ accusations. The latter is a form of unfair price discrimination whereby exported goods are sold abroad at significantly lower prices than they sell for in the home market – prices which may even be below the cost of production, hence ‘dumped’.

The measures trigger memories – or perhaps nightmares – of the trade wars seen under the Trump regime. How should we view them from our global investment standpoint?

A blip in the new low-tariff world

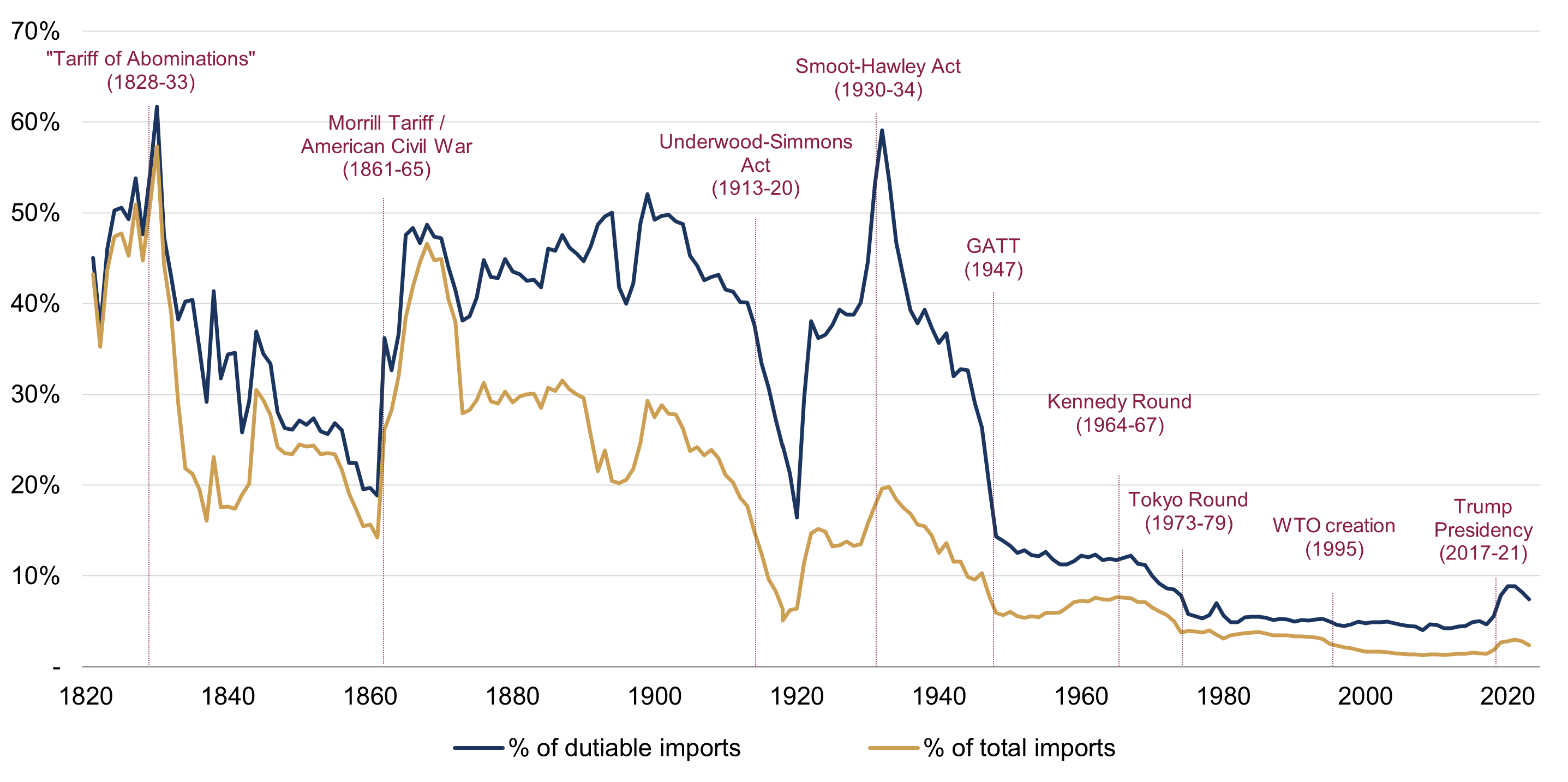

Tariffs were in fact the norm until the last few decades. Most countries used them to varying extents to ‘protect’ their domestic producers. The US itself was protected by a high tariff wall as recently as the middle of the 20th century. Its origins, during the 1800s, was the attempt to allow domestic manufacturers – particularly in the more industrialised Northern States – to compete effectively with foreign suppliers (the Southern States were actually more in favour of lower tariffs or even free trade: as big exporters of agricultural products, notably cotton, they could hardly try to protect their own markets). The revenues from import tariffs and duties accounted for a much larger share of government revenues than they do today, and it wasn’t until the introduction of US income tax in 1913 – under the Underwood-Simmons Act – that the primary source of federal revenues shifted away from tariffs.

Though such high tariffs did not prevent economic development, there were times when they had a significant restrictive effect – most notably perhaps with the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which many economic historians believe materially prolonged the Great Depression. Despite the economy already shrinking, US tariffs surged then to a staggering 60% of the value of dutiable imports, close to the highest levels ever observed (in the early 1800s – see figure 1). To make matters worse, several nations subsequently announced retaliatory tariffs on US exports – the ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies famously described by the Cambridge economist Joan Robinson.

Figure 1: A 200-year history of US tariffs (1821-2023)

Duties collected relative to the value of imports (%)

Source: Rothschild & Co, U.S. International Trade Commission, U.S. Census Bureau

Tariffs only fell sharply in the period following the Second World War, following the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 which helped to promote global trade liberalisation. More recently, the creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995 extended the approach to trade in services and intellectual property.

As figure 1 shows, the average US tariff did rebound under Trump, but it remained at historically unremarkable levels – especially when compared with the 1930 measures. Under the Biden administration, it has – until now at least – drifted modestly lower again.

US-China ‘de-risking’, not ‘de-coupling’

Viewed in this context, the US’s new tariff announcement may not be that significant. Chinese-produced electric vehicles have not accounted for a big share of US imports, and the existing tariff on them was already at 27.5%. The Inflation Reduction Act had also reduced consumer tax breaks on them. In fact, the new tariffs only cover $18 billion of US imports in total, whereas Trump’s measures overall covered closer to $400 billion.

Rather than a more comprehensive competitive challenge to China – which is of course still the more closed of the two economies – Biden’s measures feel like a continuation of his more selective ‘de-risking’ strategy, in which the US is aiming to become the leader in critical technologies. The press release stated that these measures are ‘carefully targeted at strategic sectors… unlike recent proposals by Congressional Republicans that would threaten jobs and raise costs across the board’.

Admittedly, imports from China are a much smaller portion of total US imports than they were pre-Trump, even under Biden. However, as we have noted before, this may reflect a redirection of supply chains, not a wider ‘re-shoring’: the US may be importing a greater share of goods from other Asian countries and Mexico, but China exports heavily to these nations.

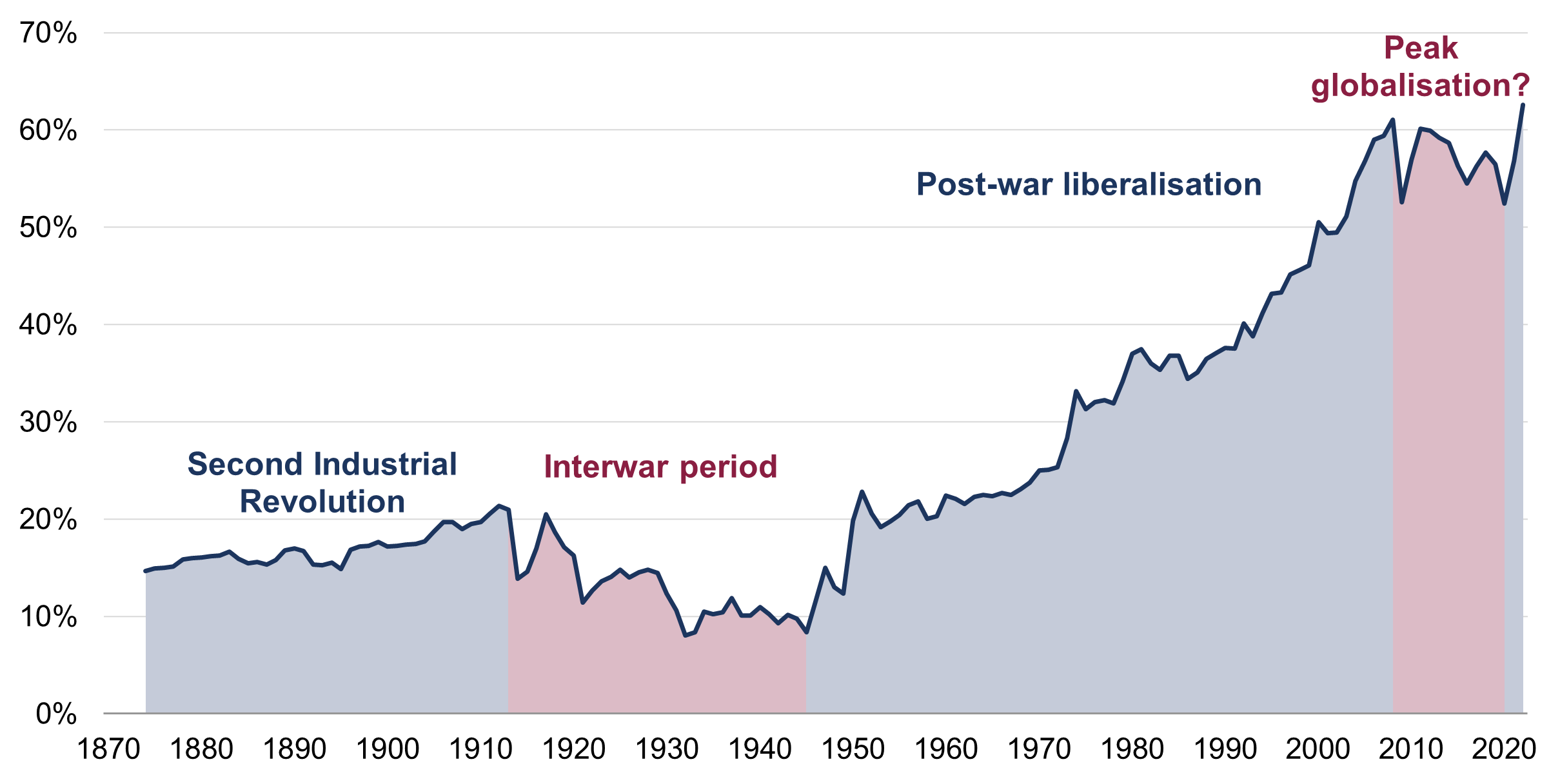

One consequence of this is that despite the Trump tariffs and much subsequent talk of ‘deglobalisation’, world trade in goods and services relative to GDP – one way to measure economic integration – rose to a fresh high in 2022 (figure 2).

Figure 2: World trade (1874-2022)

Relative to GDP (%)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, World Bank, Penn World Tables, Klasing and Millonis (2014), PIIE

The Trump risk

Of course, tariffs and protectionism might yet rise a lot further if there is a changing of the guard in November’s election.

Trump has previously floated the idea of a 60% tariff on all Chinese goods, and even a universal 10% one on all US imports. If he were to proceed with these measures, it would no doubt lead to a meaningful – and persistent – hit to GDP, and perhaps eventual deflation amid weaker demand (his proposed measures would cover more value of imports than last time).

The former president remains focused on the US’s structural trade deficit (which, by the way, widened during his tariff-heavy presidency). As we noted at the time, he has a point: China is much more ‘protected’ than the US or other developed economies. But he failed to recognise that not all of the US deficit is attributable to unfair terms of trade – much of it simply reflects strong domestic demand, for example – and by acting as undiplomatically as he did, he was taking unnecessary risks with a global trade framework which has underpinned rising global prosperity this last half century or so.

That said, it is an election year, and he often exaggerates and grandstands, and uses threats to get what he wants. For example, in 2019, his sudden threat to impose a 5% tariff on all Mexican goods imports – one of the US’s largest trading partners – came to nothing, because Mexico quickly agreed to a migration deal. He also eventually struck a trade deal with China near the end of his term – the ‘Phase One’ agreement – which cut some tariffs on Chinese goods, in exchange for Beijing buying more American exports.

It could get noisy – but disaster is far from inevitable

Falling trade barriers arguably helped foster post-war economic prosperity. Biden’s recent measures are unlikely to have a big negative impact on growth, and the lack of reaction in financial markets to the announcement suggests that investors generally agree.

Political noise will certainly ratchet up in coming months – and in 2025 if Trump gets back in. The risks of a more significant tariff-led hit to growth would then rise. But such a hit is far from a done deal. And whatever we might think of Trump, we should remember that US stocks actually performed strongly during his presidency. As we have said often, there are many moving parts in the global economy and capital markets, and tariffs are just one of them.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.